Retracing the Silk Road

Published November 20, 2006 in The Sherbrooke Record

China from West to East

At the 3752 metres high Torugart Pass, close to the China-Kyrgyzstan border crossing, we say farewell to the old Russian army truck with which we have toured for days through the beautiful hills and mountains of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. We are just in time before the pass closes until March – because of treacherous winter conditions.

From this border crossing, with its complicated and endless formalities, it is still a two-hour bus drive to the city of Kashgar, in the province of Xinjiang. It will be our first stop in the People’s Republic of China, the third largest country in the world after Russia and Canada, with a population of about 1. 4 billion people. From there, we will follow the Northern Silk Road Route further eastwards.

The Silk Road – already cultivated many centuries before Marco Polo made his passage from West to East and wrote his famous travelogue – is forced to split around the vast and barren Taklamakan desert in Central China. The Southern Route, with its hazardous mountain ranges, uninhabited deserts and extreme hot or cold spells, is more difficult to travel than its northern sibling. But in the old days, it was still the favored route by most traders since there was less chance of being attacked by bandits. It was only when the Pax Mongolia could ensure the safety of merchants, that the flatter Northern Route, more practical in an era when camels, horses, and donkeys were the only means of transportation, became the predominant trade route.

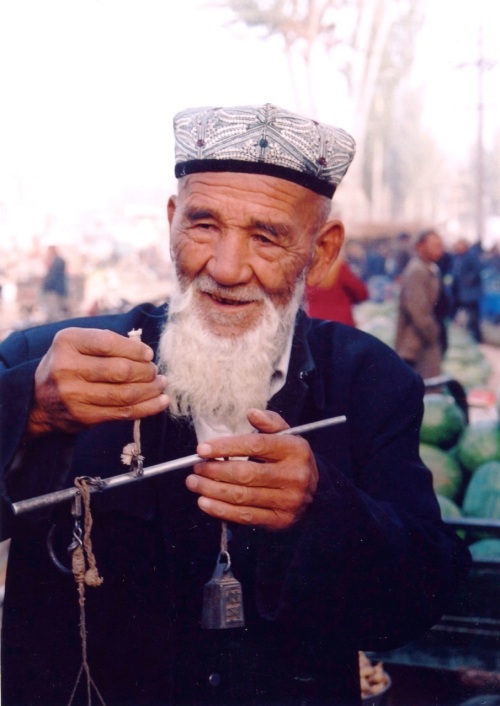

To our big surprise, there is not much “Chinese” about the province of Xinjiang. Everywhere we look, we see little mosques and minarets, heavily veiled women, and texts in Arabic characters. Families in carts are pulled by donkeys, and the smoke of kebab stalls dominates the street scene of Kashgar. While browsing through the little alleys of the inner city, one gets the sense of stepping back in time. This is the territory of the Muslim Uighurs, descendants of the Blue Turks from Lake Baikal, who probably arrived in China in the 5th century BC.

Of the 12 million Muslims in China, about 5 million people live in the province of Xinjiang. Although the Chinese government keeps encouraging Han Chinese to establish themselves in this area – by providing bonuses for instance – they have not been very successful, and the two populations hardly mix. Whereas the Uighurs mainly live in the old city (as small merchants) or in the country (as farmers), the few more prosperous Han Chinese inhabit the modern apartment buildings that slowly appear in the outskirts of the city.

At our next stop, Turpan, about 1,500 km. eastwards, and the hottest city of China, the picture is not very different. Apart from Chinese flags on government buildings and market people slurping a quick noodle soup in the early morning, Muslim life is still predominant in this wine region. That is especially apparent in the many festivities marking the end of Ramadan. Everywhere we walk, we encounter lots of people visiting each other and celebrating together with food, wine, music and dance. Hospitality is easily extended to foreigners, as many Uighurs open their doors to us and proudly invite us to their dinner tables full of the most wonderful dishes, breads and drinks.

Some modern influences have infiltrated here, however. Nearly everyone has a cellphone, and for those who don’t, the red public telephones of China Telecom are readily available on tables along the main streets and markets, in between barber shops and stalls with sheep heads, wedding dresses, fruits and vegetables.

It is only in Central China, in Dun Huang, home to the famous Mogao Caves, and set against a dramatic landscape of spectacular sand dunes, that we begin to feel we are really in China. We spot Chinese characters on the street signs and shops, we eat typically Chinese meals such as hotpot, we visit temples and pagodas, and partake in tai chi classes in the park at 7 am. And then there is of course the traditional burping and spitting all around.

Here in Dun Huang, and later in “booming” Xi’an and Beijing, we also encounter more and more signs of Western influences: rows of big apartment buildings, shops with English names such as Frog Prince, Dancing Wolves or Grey Mice, and billboards with mostly Western-looking models. There are many ATMs and banks along the main avenues, and we see European cars and American SUVs, modern hotels, boutiques and cafe’s. Restaurants try to entice us with signs like Grasp the Meat, Friendship Cafe, or Capuccino at Shirley’s, and keep reminding us of upcoming Halloween.

In the numerous narrow alleyways behind the wide avenues of these cities, the interests of ordinary Chinese are of quite another order, though. As their crumbling hutong neighbourhoods threaten to disappear in the name of “progress”, they are confronted with a standard of living they cannot always afford with the little trade-off money they receive from the government.

Our Beijing rickshaw driver Wu Meng is in good luck for the time being, as his modest living quarters will remain untouched for at least another year. In fact, his standard of living went up a notch, as city officials have recently installed private toilet pots in the communal washrooms. He now ostentatiously carries his own red toilet seat under his arm, whenever he crosses the alley to pay a visit to the loo.

If it was up to Wu Meng, that’s as far as the city’s progress should go. For on cold days, he wants to keep warming his hands at the hotpot stall of his brother next door, and in the evenings he likes to continue playing mayong with his buddies in the neighborhood cafe around the corner.

Filed under: articles | Leave a Comment

Tags: beijing, china, silk road, xinjiang

No Responses Yet to “Retracing the Silk Road”